.jpg)

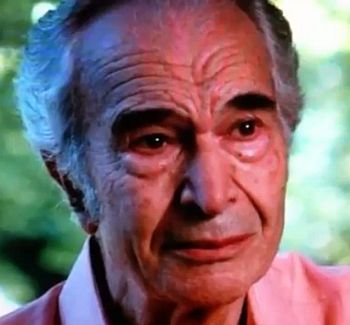

Tributes to Dave Brubeck after his death.

This moving and very special tribute was written by Chris Brubeck and posted on his blog shortly after the death of his father.

Some fathers and sons are lucky enough to have great relationships from childhood to the very end. I’m in that fortunate group. My dad and I did many fantastic things together, from playing  bond when Dave came brimming with enthusiasm to the premieres of orchestral pieces I had been commissioned to write. At this age many in my generation are experiencing the loss of their parents. My situation is a bit different than most because not only did I lose a father, but I lost a dear friend and musical partner. We have been recording, performing, and writing together for over 40 years.

bond when Dave came brimming with enthusiasm to the premieres of orchestral pieces I had been commissioned to write. At this age many in my generation are experiencing the loss of their parents. My situation is a bit different than most because not only did I lose a father, but I lost a dear friend and musical partner. We have been recording, performing, and writing together for over 40 years.

The last recording my dad made was Triple Play - Live at Zankel Music Center with my eclectic Blues/Jazz/Folk/Funk group. Believe it or not, Dave would still get nervous, even at 90! He was our musical guest and we wanted him to play loose and relaxed. Therefore we didn’t tell him we were secretly recording the concert. Sometimes, you gotta roll the dice. He played his ass off! Weeks later he told me he wished we had recorded that gig. What a joy it was to play the tapes for him of the concert he thought was lost to the ethos. He agreed it was damn good and exciting enough to share with others. The terrific reviews prove it is not just a proud son singing his dad’s praises.

One of the last concerts my father played was with me and my brothers on Father’s Day, June 19, 2011, at Ravinia outside of Chicago. I think it was fitting that our father, the family man, played his last American gig with his sons. My youngest brother Matthew plays jazz cello, Dan is on drums, Darius is also on piano, and I’m on electric fretless bass and trombone. It was a joy to perform Dave’s inspiring compositions. We made some beautiful music together, got a great review from the Chicago Tribune and then our old man went to Montreal for his last gig before “hanging up his spurs.”

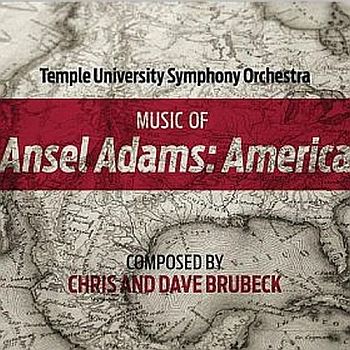

The last major piece my father and I composed together premiered in 2009. I had received a commission to write an orchestral tone poem inspired by 101 Ansel Adams photographs that  were to be projected over the orchestra. I brought my dad into the piece because I wanted to experience the joy of working with him on one more project before it was too late. Some sons go camping or on a fishing trip with their fathers when they know that time is winding down. I wanted to create a new musical work with my dad. He insisted he was too old to get involved, but my wife and I got my mother to read Ansel Adams’s autobiography to Dave. He started to see the similarities between Ansel and himself: The fact that Ansel was a budding concert pianist before he became a photographer was enticing. So was the fact that both Dave and Ansel grew up in Northern California. Both had learning disabilities that were greatly alleviated through the process of learning to play the piano. Their creativity germinated in relative isolation (my dad grew up as a cowboy on a 45,000-acre ranch and Ansel fell in love with the stunning landscapes of Yosemite) and their talents helped to transform their genres and built bridges that delivered a new perception of jazz and photography as “legitimate” art forms. Dad resonated with Ansel Adams’s story and finally we won him over. I am proud of the piece we composed together which has been played dozens of times and just had its very successful European premiere. Dad was too frail to make the West Coast premiere, but was finally able see a performance for the first time when the Temple University Orchestra played Ansel Adams:America at Lincoln Center. An excellent recording was made by the gifted young players at Temple and it was released a few months ago. But the story doesn’t end there.

were to be projected over the orchestra. I brought my dad into the piece because I wanted to experience the joy of working with him on one more project before it was too late. Some sons go camping or on a fishing trip with their fathers when they know that time is winding down. I wanted to create a new musical work with my dad. He insisted he was too old to get involved, but my wife and I got my mother to read Ansel Adams’s autobiography to Dave. He started to see the similarities between Ansel and himself: The fact that Ansel was a budding concert pianist before he became a photographer was enticing. So was the fact that both Dave and Ansel grew up in Northern California. Both had learning disabilities that were greatly alleviated through the process of learning to play the piano. Their creativity germinated in relative isolation (my dad grew up as a cowboy on a 45,000-acre ranch and Ansel fell in love with the stunning landscapes of Yosemite) and their talents helped to transform their genres and built bridges that delivered a new perception of jazz and photography as “legitimate” art forms. Dad resonated with Ansel Adams’s story and finally we won him over. I am proud of the piece we composed together which has been played dozens of times and just had its very successful European premiere. Dad was too frail to make the West Coast premiere, but was finally able see a performance for the first time when the Temple University Orchestra played Ansel Adams:America at Lincoln Center. An excellent recording was made by the gifted young players at Temple and it was released a few months ago. But the story doesn’t end there.

When my father had a heart attack on the morning of December 5, he was just one day shy of his 92nd birthday. After a Christmas concert with Triple Play in Nebraska the night before, I was driving on a highway to the Omaha airport when I got a call from my wife, Tish, telling me that my dad had been rushed to the hospital by ambulance. About a half hour later a second call delivered the numbing news that he didn’t make it. The highway just kept coming at me in hypnotic rhythm as I tried to wrap my head around this new reality. I always thought Dave would go on tour sometime and just never come back. He belonged to the road and to the world, it seemed, as much as he belonged to our family. It was surreal, he wasn’t on the road this time but I was–literally. After five hours in the car and two flights, I finally got home to my parents’ house pretty late at night. There was a tearful reunion with my family comforting each other with loving hugs. About midnight Tish and I got back to our own house nearby. I opened up my computer for the first time that day and was overwhelmed by the emails that cascaded in from all over the world. One caught my eye because it said “Congratulations.” This seemed a bit out of place, so I opened it. This is how I learned that just hours after my dad left the planet Ansel Adams:America had received a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Composition. This felt like my dad was winking at me, grinning and giving me a congratulatory hug from the other side. It was a beautiful lift when my spirits were sagging and it helps me believe in magic and miracles and to keep looking at life in a positive light. My dad always did. He overcame a lot of things and had tremendous inner strength. He loved the old standard “Sunny Side of The Street” and just for kicks he would often romp through it with unbridled joy.

For those of you who didn’t know him, here are some things I learned from my “old man” that might interest you and maybe even help you as you try to lead a musical life path.

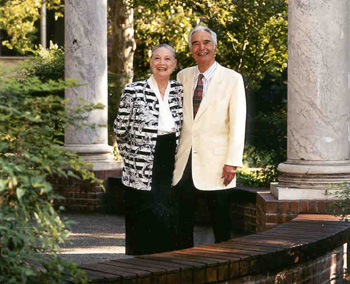

Find a great parnter to share your life with.

In my dad’s case it was my mother, Iola Whitlock. Because his mother, my Grandma Bessie, insisted he endure one of college’s rituals, he reluctantly went to the senior dance. My dad was  already doing lots of little jazz gigs. He was happy playing but very uncomfortable at the thought of dancing. Therefore, he asked around the campus to see who was the smartest and most intelligent conversationalist. Turns out that there was a drama major named Iola Whitlock who was smart as a whip and beautiful too. Iola and Dave went to the dance, talked all night, never danced, and when the sun came up had decided then and there to get married. Over the decades she supported my father’s dreams, wrote a lot of great lyrics and librettos, and never doubted his creative vision. She even managed him at first, and was the first person to come up with the idea of presenting jazz on college campuses. She somehow found the time to raise us six kids, too! My parents were married an astounding 70 years, and what a spectacular adventure they had!

already doing lots of little jazz gigs. He was happy playing but very uncomfortable at the thought of dancing. Therefore, he asked around the campus to see who was the smartest and most intelligent conversationalist. Turns out that there was a drama major named Iola Whitlock who was smart as a whip and beautiful too. Iola and Dave went to the dance, talked all night, never danced, and when the sun came up had decided then and there to get married. Over the decades she supported my father’s dreams, wrote a lot of great lyrics and librettos, and never doubted his creative vision. She even managed him at first, and was the first person to come up with the idea of presenting jazz on college campuses. She somehow found the time to raise us six kids, too! My parents were married an astounding 70 years, and what a spectacular adventure they had!

Value what is original about your approach to music.

Value what is original about your approach to music.

Value what is original about your approach to music. After World War II, my dad studied at Mills College on the GI Bill with the French composer Darius Milhaud. Milhaud had fled the Nazis when they took Paris and ended up in California teaching at Mills. My father had dreams of learning how to write in the sophisticated European tradition. Milhaud scolded him, saying that the only original thing about American music was jazz and he should try to incorporate that wonderful language into the symphonic realm. My dad followed his advice, eventually teaming up with Leonard Bernstein in some of the earliest collaborations that featured the integration of the classical and jazz genres. Dave went on to write many beautiful cantatas for orchestra, chorus, and jazz group.

Stick to your guns.

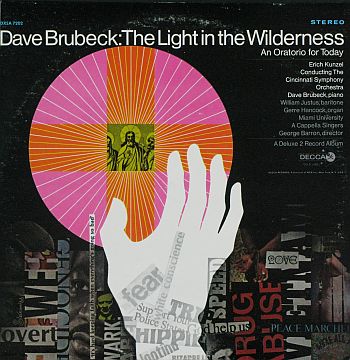

Dave had exactly two lessons with Arnold Schoenberg in L.A. At the end of the first lesson he was told to write something and bring it back for the second lesson. Dave was proud of what he wrote and when he played it for Schoenberg the next week, A.S. stopped him in the first bar  demanding to know why Dave chose the 2nd note he had written. My dad replied “because it sounded good.” Schoenberg went on a tirade saying that that was not a good enough reason to choose a note. Dad dared to ask what made him the sole arbiter of what was a right or wrong note. Schoenberg pointed to the tall book cases filled with scores that lined his studio and said he knew more about Western music than anyone else alive and that is why he had the authority to enforce his musical opinions. For better or worse that was Dave’s last lesson with the great Schoenberg. The rest of dad’s life he kept creating his melodies because of their emotional meaning to him. His intuitive melodic and harmonic instincts served him well and as a member of his band I have witnessed him improvise gorgeous and moving music countless times. When I heard this passionate music come out of him (and Milhaud was also impressed by this innate ability) it would occur to me that my dad was a genius. Thinking back though, in my father’s first major oratorio, The Light In The Wildnerness, which is a very tonal piece based on the teachings of Jesus, he created a passage where the twelve disciples were introduced by each singing their own note in a twelve-tone row. It was quite dramatic especially when Judas starting singing “Repent” on a high and straining dissonant note. So something rubbed off from his Schoenberg encounter.

demanding to know why Dave chose the 2nd note he had written. My dad replied “because it sounded good.” Schoenberg went on a tirade saying that that was not a good enough reason to choose a note. Dad dared to ask what made him the sole arbiter of what was a right or wrong note. Schoenberg pointed to the tall book cases filled with scores that lined his studio and said he knew more about Western music than anyone else alive and that is why he had the authority to enforce his musical opinions. For better or worse that was Dave’s last lesson with the great Schoenberg. The rest of dad’s life he kept creating his melodies because of their emotional meaning to him. His intuitive melodic and harmonic instincts served him well and as a member of his band I have witnessed him improvise gorgeous and moving music countless times. When I heard this passionate music come out of him (and Milhaud was also impressed by this innate ability) it would occur to me that my dad was a genius. Thinking back though, in my father’s first major oratorio, The Light In The Wildnerness, which is a very tonal piece based on the teachings of Jesus, he created a passage where the twelve disciples were introduced by each singing their own note in a twelve-tone row. It was quite dramatic especially when Judas starting singing “Repent” on a high and straining dissonant note. So something rubbed off from his Schoenberg encounter.

Being a composer is hard work.

My dad fell way short in the carousing department. He left that to his friend and musical partner, Paul  Desmond. They lived vicariously through each other, Paul being the swinging jazz bachelor with a penchant for Dewars Scotch and serial, intelligent, cutting-edge women. I think a part of Paul always thought of us kids and my mother as his surrogate family. Dave would not hang out and drink or whatever with the other musicians. He would go home to his wife and kids and work. He toured so much that he learned out of necessity to start writing on airplanes. When he was home, people were amazed to see that he had an upright piano elevated on woodblocks so that it would be at the best height for him to ride his stationary bike and pump his legs quickly while he simultaneously practiced piano and composed. That man could compress time one way or another.

Desmond. They lived vicariously through each other, Paul being the swinging jazz bachelor with a penchant for Dewars Scotch and serial, intelligent, cutting-edge women. I think a part of Paul always thought of us kids and my mother as his surrogate family. Dave would not hang out and drink or whatever with the other musicians. He would go home to his wife and kids and work. He toured so much that he learned out of necessity to start writing on airplanes. When he was home, people were amazed to see that he had an upright piano elevated on woodblocks so that it would be at the best height for him to ride his stationary bike and pump his legs quickly while he simultaneously practiced piano and composed. That man could compress time one way or another.

Perserverance

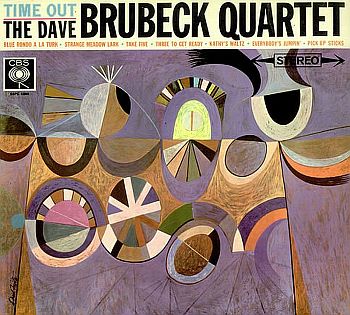

In the early days my dad was leading a group of musicians who were all former students of Milhaud. It was known as The Octet. They played very interesting music, but only got three gigs in a year. So Dave started doing trio gigs in the Bay Area. One early joint was the Burma Lounge in Oakland. Clint Eastwood told me he used to sneak in as a kid to see my old man. When dad tried to add Desmond to the group the club owner said it was ruining the band. But they stuck together and it was obvious they had a special sound and it needed to be recorded. Dad went to every record company trying to get signed. They all turned him down. We were really poor in those early days. When we went on the road, we would stay in old hotels that had cavernous closets—most times the closets were the best thing going for them. My older brothers Darius and Mike traveled with sleeping bags for those closets, that was their part of the “suite.” My parents got the bed and when I was a baby apparently I fit nicely in the dresser drawer with some blankets piled underneath me. We thought it was fun—indoor camping! We saved money up as a family because dad had to start his own record company to get his music out there. Perhaps you have heard of it—Fantasy Records! His partners were sons of a man who owned a record pressing plant. Dave supplied the talent, and they manufactured the recordings. Critics noticed, and the vinyl started moving. Then his partners screwed him out of the company. He was thrown off his own label due to some legal shenanigans. But once he was forced out of Fantasy, Columbia Records signed him and with their mammoth distribution the rest is history. By the way, his groundbreaking LP Time Out was held back by Columbia for  a couple of years because it broke all the rules. The music was in odd time signatures, it was all original compositions instead of “show tunes” (songs for which Columbia owned a piece of the publishing), and did not have a foxy girl on the cover but had modern art instead. Columbia’s marketing department didn’t know what to do with it. Goddard Lieberson intervened. That was back in the days when musicians, not lawyers and accountants, ran record companies. Goddard went against the rest of Columbia and told them to put it out. Ironically, for a long time people resented Time Out's enormous commercial success and held it against dad. But he was just pursuing his vision and created something so original that it succeeded against all odds. It all happened because he got screwed out of Fantasy Records. You never know: In the long run, a setback can be a blessing in disguise. Keep the faith!

a couple of years because it broke all the rules. The music was in odd time signatures, it was all original compositions instead of “show tunes” (songs for which Columbia owned a piece of the publishing), and did not have a foxy girl on the cover but had modern art instead. Columbia’s marketing department didn’t know what to do with it. Goddard Lieberson intervened. That was back in the days when musicians, not lawyers and accountants, ran record companies. Goddard went against the rest of Columbia and told them to put it out. Ironically, for a long time people resented Time Out's enormous commercial success and held it against dad. But he was just pursuing his vision and created something so original that it succeeded against all odds. It all happened because he got screwed out of Fantasy Records. You never know: In the long run, a setback can be a blessing in disguise. Keep the faith!

Stay humble.

Though my dad ended up playing for presidents, the Pope, kings, and queens, he never lost his respect for the average Joe. One of his favorite people to hang out with was a gardener who helped take care of things at home when dad was on the road.

This old Italian knew the earth and it wasn’t because he had a degree in botany—he just loved the land, and so did my dad. Dad grew up as a cowboy and would vividly describe to us when he used to work for a dollar a day from sunrise to sunset. He lived through the Great Depression. He made it through World War II. He could never understand how Christian civilizations that purported to follow the teachings of Christ could do such horrible things to each other. During the war, he vowed that if he lived, he would write music that would help illuminate the true teachings of Christ. He reached tens of thousands of people with his “classical music” and reminded people of the teachings of Jesus the philosopher, not Jesus the icon of “Churchianity.” He very, very rarely had an unkind word for anyone. It was a bit infuriating sometimes; he was so noncommittal in his analysis of some of the people we had to deal with. I have a more mercurial tongue and if I ever ventured a negative opinion about someone he would say, “Yes, and that is his mother sitting right behind you.” He set a very high bar in that department.

You have no idea what your music means to someone else.

We did a tour of Russia in 1987. I remember leaving at five in the morning on a bus that was in front of our hotel which would take us to the airport. It was bitter cold, and an older woman had been standing outside our bus hoping to possibly see Dave when he came out to the bus to leave. She had a medal on a chain that she gave to dad because her deceased husband had loved his music so much, and she had promised her husband that she would somehow find a way to give his medal to my father. It was very moving and I felt for this woman. Compassion about fans was bred into our family at a very early age. This is a true story:

One Christmas Eve as our family sat around in our California home in the late ‘50s my father got a phone call. He came back with a remarkable expression on his face. He told us kids to quiet down and told us a longer version of this story. Someone in New York City had just called to say that a man had crawled out on a ledge to end his life by jumping many floors to the cold asphalt below. Police officers and a police psychiatrist tried to talk the man down off the ledge but he was just so despondent they didn’t succeed. Friends were called in and asked if they would come to the apartment and try to talk to him and get him to come back inside. Nothing had worked and the situation seemed grim. Dad was called because a friend of a friend knew the person who said the words that finally got the jumper to come back inside. He apparently was told: “If you jump, you won’t hear Dave Brubeck’s next album.” That motivated the man to come back inside. Years later, this story sounds like a New Yorker cartoon, but at the time my dad was in such a state of wonderment that it made me see, from my six-year-old perspective, that we are all connected in hard to fathom ways.

A few years ago, when my dad was already older, he agreed to sit with Ken Burns and his crew  to talk about his memories and the meaning of jazz in America. I wasn’t there (madly writing on deadline across town) but later in the day I called dad and asked him how the interview went. My father told me that he blew it. I asked him what he meant by that. He said that he talked about racism in America and recalled the story of how his father, Grandpa Pete (the Cowboy), took my dad as a kid to see a man Pete knew. Pete also knew that this person had been whipped when he had been a slave. Pete told my dad that that was no way to ever treat fellow human beings. Then this fellow took off his shirt and showed little Dave his scarred back. When my dad relayed that story on camera, he got deeply emotional and cried. That’s why my dad said he blew it. But when the Ken Burns series about jazz came out, Ken himself told me that the story Dave told and his anguish which was caught on camera became the emotional centerpiece of the entire documentary. My father’s humanity came through loud and clear in that segment. Another crazy thing came out of it, too. Many of the jazz critics who saw that film and kind of enjoyed beating up my dad or dismissing him in print for his vast popularity over the last 50 years were also moved. There was a very public reassessment of Dave’s talents, originality, durability, and humanity. The family man who was too good to be true maybe really was a great guy who was too good to be true. It is not his fault that he created music that lots of people loved.

to talk about his memories and the meaning of jazz in America. I wasn’t there (madly writing on deadline across town) but later in the day I called dad and asked him how the interview went. My father told me that he blew it. I asked him what he meant by that. He said that he talked about racism in America and recalled the story of how his father, Grandpa Pete (the Cowboy), took my dad as a kid to see a man Pete knew. Pete also knew that this person had been whipped when he had been a slave. Pete told my dad that that was no way to ever treat fellow human beings. Then this fellow took off his shirt and showed little Dave his scarred back. When my dad relayed that story on camera, he got deeply emotional and cried. That’s why my dad said he blew it. But when the Ken Burns series about jazz came out, Ken himself told me that the story Dave told and his anguish which was caught on camera became the emotional centerpiece of the entire documentary. My father’s humanity came through loud and clear in that segment. Another crazy thing came out of it, too. Many of the jazz critics who saw that film and kind of enjoyed beating up my dad or dismissing him in print for his vast popularity over the last 50 years were also moved. There was a very public reassessment of Dave’s talents, originality, durability, and humanity. The family man who was too good to be true maybe really was a great guy who was too good to be true. It is not his fault that he created music that lots of people loved.

I could go on and on describing some of the great things my father did and said to many over .jpg) his 90+ years. What I have written here is the tip of the iceberg. My mother has been working on a book for the last several years and she had pretty much finished it in the last few months. She chose to end the book at the Kennedy Center Honors, which may have been the pinnacle of dad’s remarkable life. In addition to Bill Charlap, Jon Faddis, Christian McBride, Miguel Xenon, Bill Stewart, and Herbie Hancock, the producers wanted to surprise Dave by having my brothers and I play during the concert. Dave had originally requested that we play but was “turned down” by the director, to Dave’s great disappointment. However, there was a deep conspiracy between the producers and me and my three brothers. Even our own sister and my son who lives in Washington didn’t know, and certainly mom and dad had no clue that we were going to play. You can see the moment the camera caught dad in disbelief as he sat in the box next to Obama. Watch and you will see the old Cowboy mouth the words, “Son of a bitch!!!”

his 90+ years. What I have written here is the tip of the iceberg. My mother has been working on a book for the last several years and she had pretty much finished it in the last few months. She chose to end the book at the Kennedy Center Honors, which may have been the pinnacle of dad’s remarkable life. In addition to Bill Charlap, Jon Faddis, Christian McBride, Miguel Xenon, Bill Stewart, and Herbie Hancock, the producers wanted to surprise Dave by having my brothers and I play during the concert. Dave had originally requested that we play but was “turned down” by the director, to Dave’s great disappointment. However, there was a deep conspiracy between the producers and me and my three brothers. Even our own sister and my son who lives in Washington didn’t know, and certainly mom and dad had no clue that we were going to play. You can see the moment the camera caught dad in disbelief as he sat in the box next to Obama. Watch and you will see the old Cowboy mouth the words, “Son of a bitch!!!”

What a night that was. It was full cycle and poignant. Dave fought hard for civil rights in the ‘40s and ‘50s and here he was hanging out with our first African-American president. In his book The Audacity Of Hope, Obama describes his father (whom he saw only a few days in his life) taking him to see his first jazz concert in Honolulu, which happened to be my dad, my brothers, and I playing together those many years ago.

I’ll leave you with one of my dad’s favorite lines, which was what Eubie Blake said on the occasion of his 100th birthday tribute: “If I’d known I was going to live this long, I would have taken better care of myself!”

No one lives forever, my dad did his best and led an astounding life. It was great to be on that incredible ride with him.

***************************************************************************************************************

Papa Dave: Remembering Dave Brubeck

Darius Brubeck reflects on his father's passing, as well as the jazz legend's South African connections.Darius Brubeck wrote this piece for "The Mail & Guardian" - South Africa online  newspaper.

newspaper.

Dave Brubeck was still touring in the summer of 2011, but it was increasingly hard going and by early Fall it was clear that I should take over his two remaining commitments.

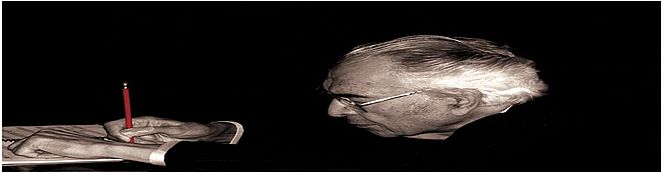

This was termed a ‘medical hiatus’ but he never played in public again. When Cathy and I arrived for an extended visit in November this year, we were sad to see how much weaker he was. Right up to his fatal heart attack, however, he was among the living and often played one of the two grand pianos in his studio.

People often become more devout or at least curious about ultimate things as they sense the end approaching, but this was not my father’s way. He took pleasure in watching the comings and goings of his vast, multi-generational family in his large, self-designed country house and reminiscing with friends, but his physical weakness and dependence on Iola, his wife of 70 years, frustrated him. I know he was ready to move on.

I asked him one day if something was irritating him and he answered, ‘life.’ Somehow the sense that Dave was nearing the end of a life well-lived reached beyond the immediate family. Herbie Hancock phoned out of the blue just for a chat. Wynton Marsalis came out from New York City for a long visit and to discuss what an all-Brubeck programme at JALC might consist of.

Dave’s near-contemporary George Wein (founder of the Newport Jazz Festival), whose long career and international brand began with Dave as his first headliner, dropped in with record producer Hank O’Neil. They sat at the white, oval Saarinen kitchen table drinking California merlot and talking about the recent US election (all life-long, fervent Democrats, of course) and the old days. There was no specific reason to expect Dave to die so soon afterwards but these occasions were goodbyes.

I lived in South Africa from 1983 to 2005, teaching jazz at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, and my wife, Cathy, is South African, so sometimes people assume Dave must have had a South African connection too. Actually there is no ancestral or other background connection, but through us, South Africa became important to him.

The New Brubeck Quartet (Dave, Chris, Dan and I) toured South Africa in 1976, of all years, albeit before the declaration of the UN cultural boycott. Dave had been an outspoken campaigner for civil rights in the American South in the 1960s and it didn’t take long for him to see that while coming to South Africa may have been a mistake, he could also make demands that might do some good.

The New Brubeck Quartet (Dave, Chris, Dan and I) toured South Africa in 1976, of all years, albeit before the declaration of the UN cultural boycott. Dave had been an outspoken campaigner for civil rights in the American South in the 1960s and it didn’t take long for him to see that while coming to South Africa may have been a mistake, he could also make demands that might do some good.

He insisted on a local opening act, Malombo and hired Victor Ntoni to play acoustic bass with us. Even though we were self-contained with my brother Chris playing electric bass, this was a way to ‘integrate’ our group. Dave later sponsored Victor at Berklee School of Music in Boston and my parents came to visit us in Durban in 1984. They really loved the country and, as always, made lasting friends.

In 1988 our jazz programme made big news because we took the first South African student jazz band, the Jazzanians, out of the country where they appeared at the International Association of Jazz Educators conference and on two major US TV networks. My parents’ house in Connecticut was the home base for this large group of South African students (Johnny Mekoa, Zim Ngqawana, Nic Paton, Rick Van Heerden, Andrew Eagle, Melvin Peters, Victor Masondo, Kevin Gibson and Lulu Gontsana).

Subsequently Dave and Iola hosted four more South African student bands and helped them with logistics, donations and friendship throughout the years. It was really special for our family to receive condolence messages from some who referred to my father as “Papa Dave”. It makes us all feel like a family bonded forever.